If you’ve seen One Battle After Another, I wonder if the car chase toward the end had an impact on you. I’m going to add a snippet of it here and hope I don’t get in trouble for hosting it. Why tempt trouble? I’m glad you asked.

You can picture many (most? all?) Hollywood car chases: speeding through urban settings, dangerous intersection crossings, careening around corners, weaving through traffic. And then there are the explosions, crashes, pedestrians diving out of the way, and the invincibility through all this by the protagonist driver. It’s mayhem. Oh, let’s not forget that if it’s a police chase scene, the eluding car always gets away. How in our modern era of cameras everywhere, helicopter flyovers, and police traps does this happen?

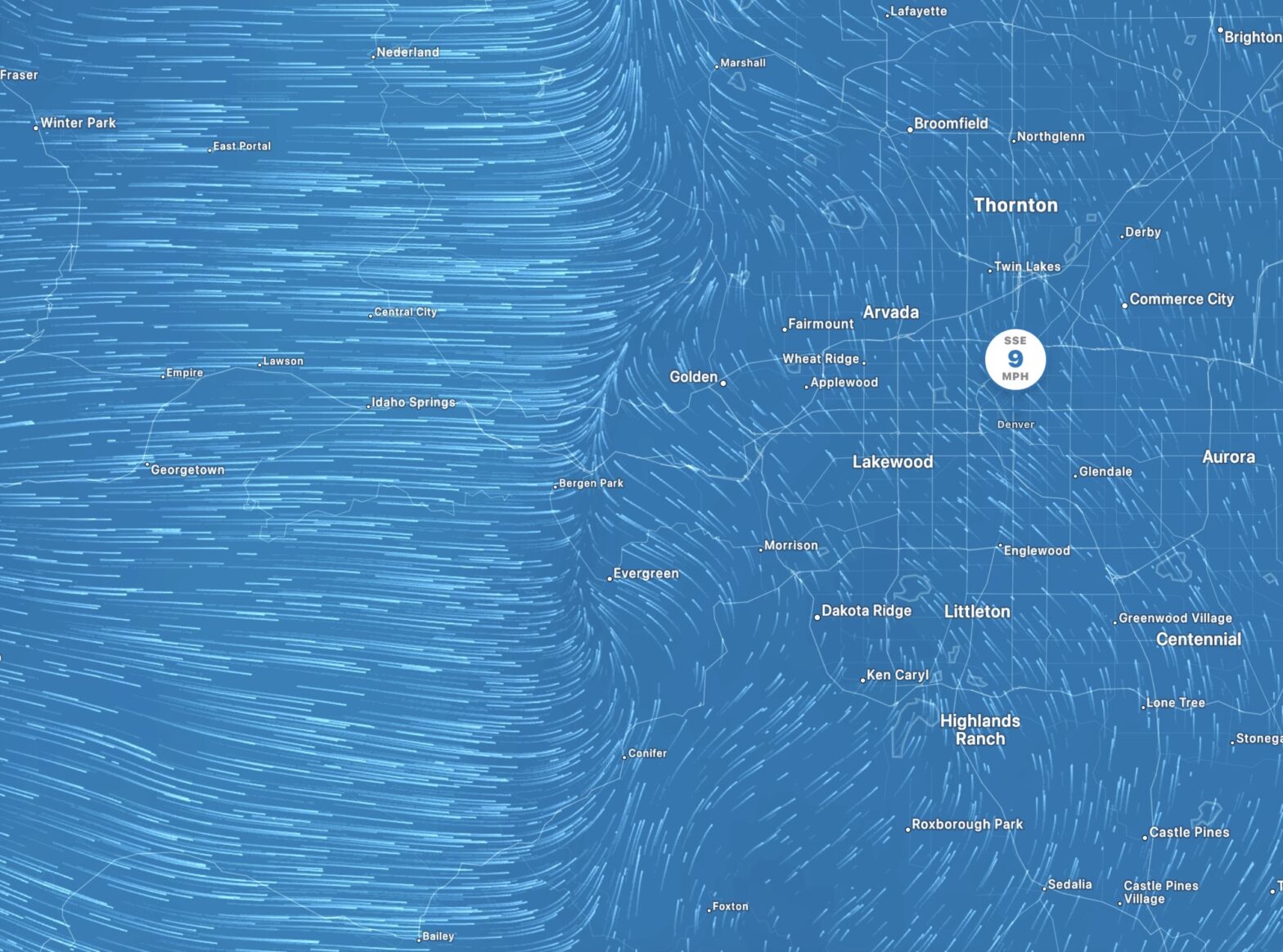

Then comes along One Battle After Another. Still some Hollywood thrown in, but much less so. The chase doesn’t seem overly fast. No corners to take at an unsafe speed. No sideswiping cars dueling for position. Just cars on a lightly travelled, hilly backwater highway. It’s the landscape that makes the chase so good. It’s as much an actor as the actual actors. It’s the hills, and in particular how they’re filmed, that’s so good.

The clip is super short (again, trying to stay out of trouble), but pay attention to how the camera work bobs us up and down. Not merely because we’ve cruising up and over hills, but because the camera exaggerates that feeling of up and down by dipping close to the pavement as the hill rises. It accentuates the cat and mouse-ness of the scene—we see the car ahead (or behind), then we don’t, then we do again. Will something change when the car is out of sight? Will we be closer, further away, will the car have made an erratic move? We’re forced to climb the next hill to find out. So good. Here’s an extra long clip (if it lasts) for more of the effect.